It’s not the same as before

It’s not the same anymore

And it’s fine becauseI’ve learned so much from before

Now I’m not sure on advice

There’s no excuses at all

No point in feeling upsetWon’t take my place on my floor

I’ll stand up straight like I’m tall

It’s up to me, no one else

I’m doing this for myselfIt’s not the same anymore

Orange Rex County

It’s better

It got better

It’s not the same anymore

It’s better

Yeah, yeah

“Everything has changed, but nothing has changed.” (Mark Hamill)

Grade 1 is now Year 2. I teach in German instead of French. My classroom isn’t a shipping container anymore but a wood-cladded portable. The bush next to the school has turned into a gigantic construction site for a state-of-the-art hospital. I live in my boss’s apartment instead of my little blue house. Drink cappuccino instead of a weird long black. And the Queen is now a man.

Everything has changed, but nothing has changed.

It’s been almost a month since I returned to the Northern Beaches of Sydney, and the strangest thing is that it’s not strange at all. I take the same bus to work, greet the same people (now hidden behind mandatory face masks), and make my way to school, where I am still always the first to arrive. Turn on the light in the staff room and the heat (yup, still chilly in the mornings) and start my day. Get my coffee at the same café across the street, shop at the same shops, buy my bread at the same bakery, and watch the same sun rise in the morning and set at night.

It feels the same, and it doesn’t.

There are new colleagues at school. New people I meet. New friends and old friends. My favourite Italian restaurant is now a falafel shop, and my local coffee place moved to the other end of town. In the morning, it’s the lorikeets that wake me with their ruckus instead of the kookaburra. The only thing that is still the same is my green wooden bench.

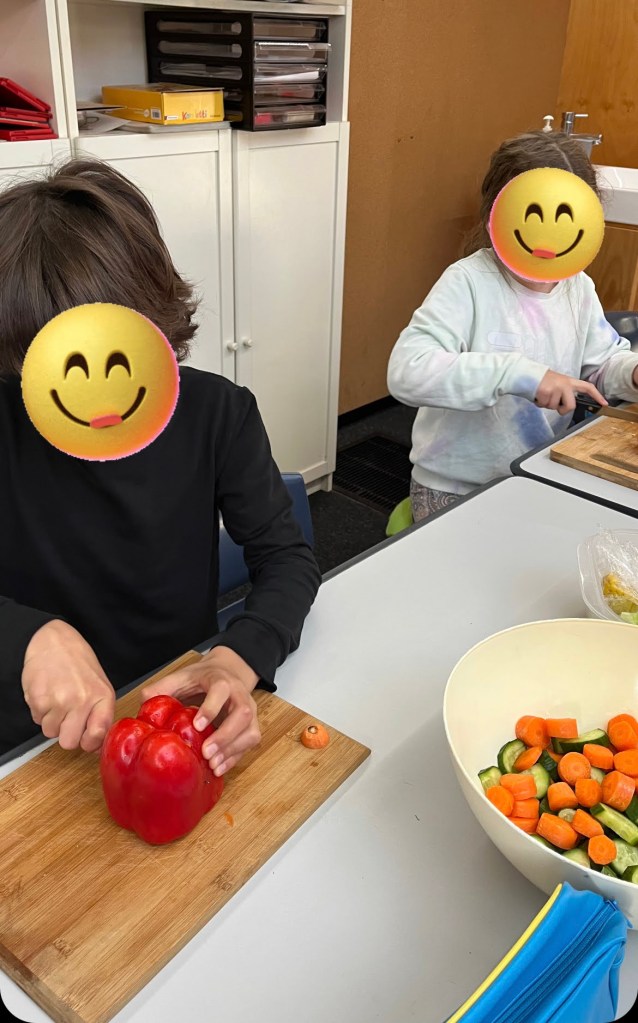

The unfamiliar familiar. In teaching, we often try to make the unfamiliar familiar. Using familiar objects to explain new and unfamiliar concepts is the key to constructivist teaching. We explain volcanos by building a volcano model, the time of dinosaurs by displaying dinosaur toys. However, many concepts cannot be made familiar by passing around plastic toys.

I was trying to teach the Creation Story to my Grade 2 Religion class this week (On Day 1, God created…, on Day 2,…) when one of my students – clearly distraught and confused – kept interrupting me by shouting: “But what about the dinosaurs? But what about the dinosaurs?” The concept of God creating ALL animals on the same day was not something that made sense to him. And it doesn’t. Trying desperately to teach an eight-year-old the difference between Creationism and Evolution, my attempt to make the unfamiliar familiar failed miserably.

Or maybe it didn’t. Meaningful learning, so they say, takes place when the learner (my bewildered Year 2 student) tries to make sense of what he or she is being taught by using all the resources they already have available, what is already familiar to them. Only in this case, knowing that dinosaurs lived way before most of the other animals, didn’t make sense to this boy at all. Teaching and learning abstract ideas isn’t always straightforward, I guess.

I finally made it to the sunrise at the beach: no rain, no work, but a familiar display of Nature’s beauty. And while I was sitting on the golden sand, still slightly wet from this week’s heavy downpours, watching the waves roll incessantly towards the shore, I realized that things are different and the same. Familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

It’s not the same anymore. It gets better.

Cheers!